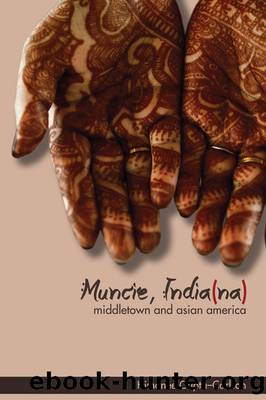

Muncie, India(na) by Himanee Gupta-Carlson

Author:Himanee Gupta-Carlson [Gupta-Carlson, Himanee]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, General, Ethnic Studies, American, Asian American Studies, History, United States, State & Local, Midwest (IA; IL; IN; KS; MI; MN; MO; ND; NE; OH; SD; WI), Emigration & Immigration

ISBN: 9780252050497

Google: SuhPDwAAQBAJ

Barnesnoble:

Goodreads: 36459732

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Published: 2018-02-21T00:00:00+00:00

Being Ourselves

âI was the most rebellious [of my siblings],â recalled Lynsi, a Muncie-raised South Asian who graduated from high school in the same year I did.

âHow were you rebellious?â I asked.

âI didnât go to the Bengali parties,â she replied. âI didnât wear the Bengali, you know, the sari. I never have. I really didnât spend any time with anyone in the culture. I dated, did things that were definitely not part of the culture.â

âI never drank. I never smoked ⦠in the American measurement that would be rebellion. I think I was just not following the expectations of the culture.â

âWhat do you mean by the culture?â I asked.

âBengali, decidedly Muslim,â she said. âVery tightly knit, you know that. Everybody knows everybody. A clique.â

Lynsi shared these observations with me when I visited her home outside Chicago. Forty years old at the time, she identified herself as an American who was Bengali by ethnicity and Muslim by religion. She was born in Karachi, Pakistan, and grew up in Muncie from the fourth grade on; she completed high school at the Burris Laboratory School and her undergraduate degree at Ball State. She moved first to Florida and later to Chicago, where she completed masterâs and doctoral degrees, specializing in criminal justice. When we reconnected, she was a professor of sociology and was completing work on a scholarly encyclopedia.

Lynsi remembered Muncie much as my sister Anju did, as a place she loved growing up in but after leaving did not want to return to live. Lynsi also remembered it as the place where she asserted herself as an individual in ways that were like her nonâSouth Asian school peers. She characterized that self-assertion as setting her apart from her parentsâ Bengali culture, and she saw that setting apart as making her appear rebellious.

Lynsiâs stories of her teenage years called up memories of my life in those years as well. My parents discouraged dating, drinking, and drug use without expressly forbidding it. They spoke of the value of their Indian culture and encouraged me to adhere to its norms of obedience to parents, particularly when it came to marriages, which they felt should be arranged. Those norms made little sense to me, so I responded by talking to boys on the phone and going over to friendsâ houses to drink beer. I did not want to âget into trouble.â I just wanted to feel like I could take part in something my friends were doing, regardless of whether my parents approved. Like Lynsi, I wouldnât wear the ethnic attire associated with my familyâs heritage, and I was not interested in getting to know anyone of Indian or other South Asian ancestry. And, like Lynsi, I went against my parentsâ expectations that I study medicine or engineering and instead pursued a passion to write.

âDid your parents know about the dating?â I asked Lynsi.

âNo. God no,â she replied with a laugh. âWell, my mom probably did. My dad may have, but I doubt it.â

âDid you date?â she asked, after a pause.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Chakras | Gandhi |

| History | Rituals & Practice |

| Sacred Writings | Sutras |

| Theology |

Fingersmith by Sarah Waters(2520)

Kundalini by Gopi Krishna(2161)

Wheels of Life by Anodea Judith(2127)

Indian Mythology by Devdutt Pattanaik(1921)

The Bhagavad Gita by Bibek Debroy(1915)

The Yoga of Jesus: Understanding the Hidden Teachings of the Gospels by Paramahansa Yogananda(1838)

Autobiography of a Yogi (Complete Edition) by Yogananda Paramahansa(1805)

The Man from the Egg by Sudha Murty(1794)

The Book of Secrets: 112 Meditations to Discover the Mystery Within by Osho(1656)

Chakra Mantra Magick by Kadmon Baal(1631)

The Sparsholt Affair by Alan Hollinghurst(1571)

Gandhi by Ramachandra Guha(1517)

Sparks of Divinity by B. K. S. Iyengar(1515)

Avatar of Night by Tal Brooke(1511)

Karma-Yoga and Bhakti-Yoga by Swami Vivekananda(1484)

The Bhagavad Gita (Classics of Indian Spirituality) by Eknath Easwaran(1469)

The Spiritual Teaching of Ramana Maharshi by Ramana Maharshi(1422)

Hinduism: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) by Knott Kim(1361)

Skanda Purana (Great Epics of India: Puranas Book 13) by Bibek Debroy & Dipavali Debroy(1360)